READING — In June, Reading City Council members were asked to sign a pledge committing to work toward the city’s new goal of zero traffic deaths by 2033.

The plan to get there, known nationally as “Vision Zero,” was years in the making, and the mayor’s office needed council approval before applying for a federal $1.2 million grant for bike lanes and transportation safety improvements downtown.

Council members expressed their support for the plan and optimism that it could help reduce fatalities.

“It’s so important that it’s not just something really worthwhile to look at and make sense, but that implementation does occur,” Council President Donna Reed said at the June 9 meeting. “Because the city, unfortunately for whatever reason, is notorious for not following through on some really wonderful plans that would have made a huge difference.”

Reed listed proposals beyond just traffic enforcement, but a Spotlight PA review found that a previous nationally recognized traffic safety plan did not work the way officials intended.

The initiative, known as “Complete Streets,” included goals such as tracking the number of bike share users, conducting business satisfaction surveys of streets and sidewalks, and monitoring the percentage of the city’s population within two miles of “low stress” bike routes.

City Council was supposed to get an annual report detailing the progress of the initiative, but members of the mayor’s administration told Spotlight PA they did not know when the task force managing the project last met. Also, the city has downsized to one traffic engineer.

Now officials want to move in a different direction. They believe they can because of the city’s exit from the state’s budget oversight program and a new state-approved tool to fund development. The city will try again to reduce car crashes under the new program, if it can chase and earn the necessary funding to follow through.

“You'll hear the sentiment in Council meetings that the city has had a plethora of plans, and they just end up on shelves,” said Jack Gombach, Reading’s managing director, who acts as representative for the mayor’s office in meetings and as the city’s chief administrative officer. “Our focus has really been consolidating those plans and then actually executing on those plans.”

Still, Gombach insisted that the city will follow through this time, even if it does not win the initial grant to get started.

Officials insist Reading’s application ‘strong’ despite error

Reading’s pitch for grant funding includes 5.1 miles of bike lanes, removable speed cushions, increased signage, and painted crosswalks in parts of the downtown area, according to a Spotlight PA review of the Safe Streets and Roads for All application.

The additions would be temporary unless the city later deems the test run successful. The grant application lists a number of success metrics, including a before-and-after count of bicycle users on the new routes, public surveys, and a comparison of crash data over a year’s time.

The city applied for a grant under the same program in fiscal year 2024 but did not get the funds. Spotlight PA requested a copy or synopsis of the past proposal but one was not provided by the time of publication.

The federal Department of Transportation, in charge of awarding the grant, prioritizes cities with fatality rates of around 17 persons per 100,000, according to the application Reading submitted. Reading said it should still be eligible for the grant despite not meeting that threshold because of its high poverty and traffic fatality rate of about 10 persons per 100,000.

However, Spotlight PA discovered the consultants and city employees who prepared the application and Vision Zero report listed two different rates in each document. The application listed an average fatality rate of 10.3 persons from 2018-2022. The actual fatality rate was about 5.04 persons — half of what they submitted in the original application and slightly higher than the 4.9 persons listed in the report.

The project consultant said he would submit corrections to both documents.

Tiffany Smith, a program manager with Vision Zero Network, was unsure how editing the application would affect Reading’s eligibility. The network is a national nonprofit that advocates for car-alternative transportation policies and helps connect participating communities.

Gombach said he does not anticipate the error will affect the application. He also expects any changes to downtown, once proven successful, to become permanent.

“At the end of the day, it's still a very strong application, even with the corrected numbers,” Gombach said. “And it's comprehensive to what we're trying to do, not just in our downtown, but in our city.”

Smith said the specific type of grant, known as a “demonstration grant,” can be easier for cities to get than others.

Many use it to test-drive ideas. This can take the form of more experimental projects like installing speed-tracking systems into the cars of repeat offenders. Or it can be a way for cities to fund systems to pilot safety measures without committing to the full cost of permanent installation, Smith said.

Downtown Reading is not populous, but the grant application argued the neighborhood’s residents are some of the most cost-burdened in the city and have some of the highest transportation costs, making it an ideal location for bike lanes and increased safety measures.

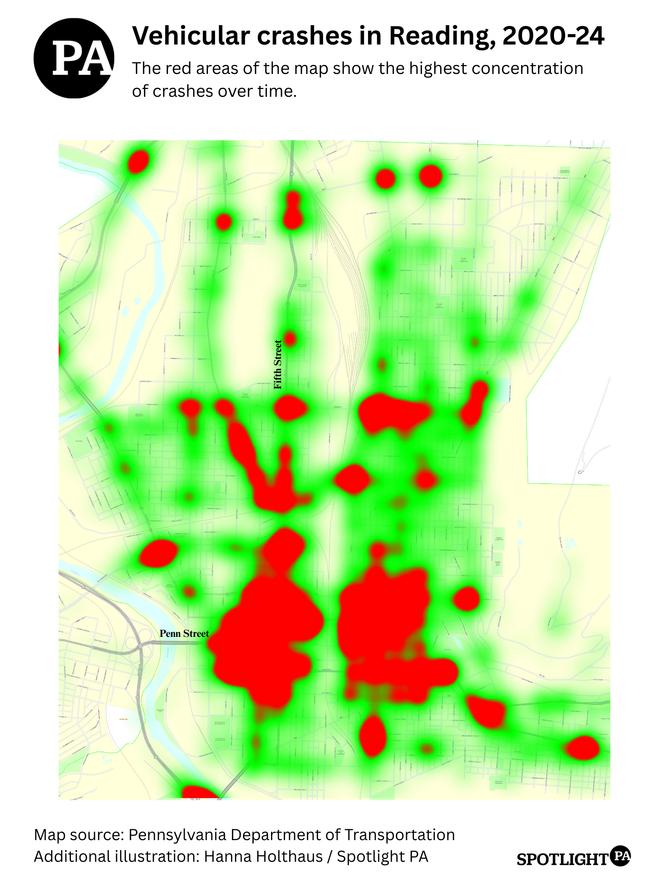

The application also cites a “high number” of crashes at downtown intersections, but does not specify if those are the city’s most dangerous.

Smith said cities usually address the highest crash zones first as they apply for grant funding. Those areas regularly may intersect with disadvantaged neighborhoods, Smith said.

“It's a good thing in the sense of what we do see usually in trends is that high poverty communities are overrepresented in deaths and severe injuries,” she said.

The most successful projects nationally have community buy-in, Smith noted. She advised the city to look for small wins, be responsive to feedback, and pay attention to statistically proven safety measures.

City officials expect to find out in the fall if they won the grant. They will have one year to complete the project if the funding is approved and contractually will have to dedicate $300,000 of city funds.

Lessons from other Pa. communities

Having a dedicated Vision Zero coordinator and active planning team (normally made of community stakeholders) is essential to progress, Smith advised. She had never heard of a city with Reading’s population size having only one traffic engineer, but other members of a planning team can help as well.

There are more resources available to cities now than in 2015 when Reading passed its Complete Streets plan, Smith said. She recommended the city look to its neighbors and replicate what has been successfully completed.

The City of Lancaster and the City of Bethlehem received $12.7 million and $9.9 million, respectively, in 2023 through the same federal grant program Reading applied to in June.

Lancaster’s plan takes a broad approach. The city planned to use the funding to strategically convert some roads to two-way streets to calm traffic, create school safety projects, and update crosswalks, among other actions.

Bethlehem adopted its first plan in 2016 and is using the grant to narrow its main West Broad Street corridor by adding protected bike lanes, crosswalk improvements, and public transportation options.

The average fatality rates for both cities have mostly remained the same since each Vision Zero plan passed, according to a Spotlight PA review of federal crash data. However, program coordinators from both cities said the federal grants will allow them to complete larger-scale projects.

Crash data are not hard to track, but it takes time to analyze and find trends, said Cindy McCormick, deputy director of Lancaster’s Department of Public Works. The city has seen the raw number of crashes go up and down in the years since taking up Vision Zero, but officials largely focus on making the roads safer for vulnerable road users such as cyclists and pedestrians.

Education and outreach take time, McCormick said. She recommended Reading look for low-cost projects to build momentum as they go for bigger and broader grants.

Sherri Penchishen, the Bethlehem coordinator, has worked for the city for 29 years and overseen the Vision Zero program from its inception. Bethlehem’s traffic advisory committee already had been meeting since the 1990s, so converting to the new program was a cinch, she said.

The group met monthly for years but recently transitioned to every other month, Penchishen said. That collaboration between city, state, nonprofit, and residents is what has made the program successful, as well as allowed them to jump at opportunities as they come up, she said.

Penchishen told Spotlight PA that most of the city’s projects have been funded through grants, a product of the task force having projects planned at all times. Whenever grant funding becomes available, she said, the city can submit a timely application.

“Because we meet so frequently, we're always working on a project, and we're always doing something, always having outcomes,” Penchishen said.

Back in Reading, Gombach said he does not expect the city’s Vision Zero task force to go the way of past projects. Although the group that helped develop the initial plan has not met since its approval, he said, he plans for it to start convening again after the city learns if it got the federal grant.

Reading will continue working toward the project even if it does not get the money, but not securing the funding would require some adjustments to the city’s project timeline, Gombach said.

“What we've seen so much in Reading’s history is we start, start, start, and then there's turnover,” Gombach said. The current administration is hoping to institutionalize Vision Zero, downtown revitalization, and transit plans, he continued.

“How do we make it more entwined and more leading the day-to-day so it can withstand those changes in leadership?”