Spotlight PA is an independent, nonpartisan newsroom powered by The Philadelphia Inquirer in partnership with PennLive/The Patriot-News, TribLIVE/Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, and WITF Public Media. Sign up for our free newsletters.

HARRISBURG — It’s showtime for Pennsylvania’s brand-new legislative districts.

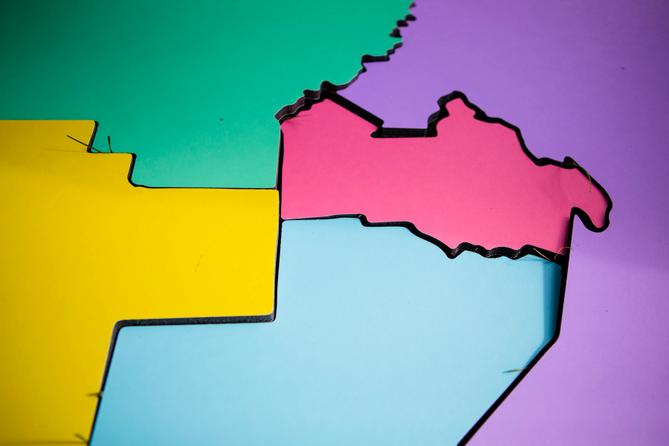

The revamped state House and Senate lines were approved by a commission made up of legislative leaders and an independent chair, and unanimously upheld by Pennsylvania’s highest court as part of the latest decennial redistricting process.

The maps helped spawn a wave of retirements that have already reshaped the 253-member Pennsylvania General Assembly, a preview of changes the Nov. 8 election may bring.

These untested new district lines could give Democrats a long elusive majority in the House, potentially shifting the balance of power in the legislature. Or the new maps could maintain the status quo of Republican control.

Below, Spotlight PA breaks down three things to watch for Nov. 8:

Fewer competitive districts (but those that remain are more competitive)

Following this year’s redistricting cycle, both the state House and Senate ended up with fewer competitive seats.

Experts score political maps for competitiveness by predicting future results based on past election cycles. According to Dave’s Redistricting App, a nonprofit map analysis website, just under 40 seats in both chambers could be classified as competitive — meaning neither major party has an overwhelming majority in a district — compared to nearly 60 in the previous maps.

This is in part due to the population shifts over the past decade. More people left rural areas and moved into urban and suburban regions, which traditionally lean Democratic.

Creating competitive districts isn’t required under the Pennsylvania Constitution, but it’s a top priority for the many citizens and advocates who have lobbied lawmakers to make the process more inclusive and transparent. Over 6,000 voters identified competitive elections as a top priority in a survey conducted by Draw the Lines, a redistricting project of the Committee of Seventy, a good-government advocacy group.

While both maps saw an overall decrease in the number of competitive districts, they are now more representative of the partisan composition of the state, according to Dave’s Redistricting App.

Increasing the number of competitive districts would have required manipulation of Pennsylvania’s political geography — or the way that voters are concentrated or dispersed across the state — and would have affected districts’ compactness, contiguity, and equal populations, which are all requirements under the state constitution. The artificial creation of more competitive districts also would have influenced the partisan fairness of the map.

“You want competitive districts, but in some districts, you can’t have that,” said Justin Villere, the executive director of Draw the Lines. He used Philadelphia as an example, where more than three-quarters of voters are registered as Democrats.

The competitive districts in the new legislative maps are concentrated in the Pittsburgh and Philadelphia suburbs, with a sprinkle of other competitive races in the Lehigh Valley and around Harrisburg, Erie, and State College.

They contain a slightly higher percentage of independent voters on average compared to the 2020 maps, according to Dave’s Redistricting App, indicating a larger number of voters who are willing to vote for either major party come election time.

The new legislative maps also have a higher level of responsiveness — meaning that these maps are more likely to create a General Assembly that reflects the vote share in each election cycle.

“Responsiveness is essentially the opposite of partisan advantage,” said Villere.

Democrats have a better chance in the state House

Operatives in both major parties agree that Democrats are likely to shrink Republicans’ 111-92 advantage in the state House because of the new lines.

Under the old map, 80 seats leaned Republican and 78 leaned Democratic, according to Dave’s Redistricting App. The rest were classified as competitive, with the electoral margin between the parties typically being less than 10 percentage points.

Under the new map, 81 seats favor Republicans and 95 favor Democrats. While Republicans nearly built a supermajority in the lower chamber in recent years, the new lines indicate Democrats will likely secure a larger share of the seats due (barring a major shift in voting patterns among the electorate.)

Why this dramatic shift occurred depends on who you ask. All will agree this is in part because of population shifts from the more rural west to the more suburban and urban east.

Democrats — backed by independent analysts — add that the previous maps were drawn to aid Republicans. While Democrats regularly win statewide races, they haven’t had control of a legislative chamber since 2010.

Republicans counter that comparing statewide results and 253 individual races is like comparing apples and oranges, and argue that the old map was designed to protect western Pennsylvania Democrats who simply couldn’t survive the post-Trump political realignment.

The GOP has acknowledged that the new lines will likely cut into their margin, but it’s still an open question whether Democrats can flip the chamber.

“There’s not a doubt that the redistricting process was favoring Democrats,” state Rep. Josh Kail (R., Beaver), who leads House Republicans’ campaign efforts, said. “With that being said, we have a better message, we have better candidates, and we’re going to win races, period.”

Pittsburgh’s northern suburbs, which include a mix of affluent neighborhoods and old industrial river towns, are some of the best bellwethers of which party will procure a majority.

Redistricting created two open, competitive House districts — the 33rd and the 30th — in the area, which boasts strip malls tucked into hollows and homes built into hillsides.

The latter will be represented by either Democrat Arvind Venkat, an emergency room doctor, or Republican Cindy Kirk, a former Allegheny County council member.

The area’s previous districts reliably elected Republican legislators, including former House Speaker Mike Turzai, a stalwart conservative. However, some municipal seats have begun to flip from red to blue, and Democrats hope they can finally break through on the state level.

At a community festival in McCandless last month — the heart of Turzai’s old district — Venkat greeted voters and pitched himself as a candidate who would protect abortion access, pass stricter gun laws, and invest in public services stretched thin by the pandemic.

“There’s a real hunger for new leadership that will make sure that the state government is working for everyone in our community,” Venkat said.

Kirk did not agree to talk to a reporter at the same event and did not respond to further requests for comment. Her website emphasizes her health care background, noting that she worked as a UPMC nurse administrator. Her site also trumpets her opposition to new taxes and support for police, and says that Kirk will “push back on the progressive agenda and defend our constitutional rights.”

Other key races are taking place outside Philadelphia, where some of the last suburban Republican moderates are up for reelection in redrawn districts that are now slightly bluer. That includes state Reps. Todd Stephens (R., Montgomery) and Chris Quinn (R., Delaware), both of whom have regularly won even when their districts voted for Democratic presidential candidates by double-digit margins.

“I have always represented a swing district,” Quinn said in an email.

He argued he’s done so by working across the aisle and bucking his own party when “I have felt that their direction is not in the best interest of my district.”

In order to win, Democrats must convince Pennsylvania voters not to split their tickets. In 2020, voters in key suburban districts backed President Joe Biden while also voting for numerous down-ballot Republicans like Auditor General Tim DeFoor as well as their local Republican legislators.

“If folks are looking at their choices and they don’t like the extreme policies of Doug Mastriano, they need to vote straight Democrat, because we’ve seen those same policies passed by the Republican majority in Harrisburg,” said state Rep. Leanne Krueger (D., Delaware), who leads House Democrats’ campaign efforts.

Opportunity districts don’t look so opportune

Lawmakers charged with drawing the new state House and Senate maps have emphasized a desire to increase minority representation in the General Assembly, citing the sharp increase in the Hispanic population according to the 2020 census.

Lawmakers saw opportunity districts as the vehicle to achieve that representation. Opportunity districts have a minority voting age population that is sizable enough to sway an election (a threshold that is typically around 30% of a given electorate) — and are typically drawn without an incumbent.

There were 11 new opportunity districts without incumbents drawn in the redistricting process. The Lehigh Valley, which has a high Hispanic population, notably contained one of those districts.

In a previous analysis of five races in opportunity districts, Spotlight PA found that candidates of color were motivated by open seats that lacked an incumbent rather than the racial makeup of the district in which they planned to run.

The demographic composition of these districts generally did not overcome a more deep-rooted disadvantage. Three of the five candidates lost their primaries, typically to candidates who had more or prior experience in politics and all of whom were white.

Two candidates moved forward to the general election: Democrats Justin Fleming of Dauphin County and Yesenia Rodriguez of Luzerne County, who ran unopposed during her primary.

Fleming, who’s running in a majority-Democrat district, has worked in state government as a press secretary and commissioner in Susquehanna Township.

Rodriguez, meanwhile, primarily runs a bakery and has little political experience outside of an unsuccessful run for a local school board in 2019. She’s also running as a Democrat in a majority-Republican district with little funding. Campaign finance records from the Pennsylvania Department of State show that Rodriguez has raised just over $1,000 this year.

Her opponent, Dane Watro, has been endorsed by several big-name establishment Republicans, including Pennsylvania’s former U.S. Reps. Lou Barletta and Dan Meuser, and state Sen. Dave Argall of Schuylkill County.

Watro, who did not respond to requests for comment, had nearly $30,000 in available funds as of June and raised more than double that over the course of his campaign.

Despite the voter registration and financial disadvantage, Rodriguez said that her connection to the residents in Hazleton, where she has lived for the past two decades, will help her win. The city is the second largest in Luzerne County and one-third of its population is Hispanic.

She also emphasized her effort to directly talk to each resident in her district, including in more rural areas.

“Money doesn’t buy votes,” said Rodriguez. “Even though we don’t have the money and we didn’t get the support from major companies or institutions … we have done the job ourselves.”

WHILE YOU’RE HERE… If you learned something from this story, pay it forward and become a member of Spotlight PA so someone else can in the future at spotlightpa.org/donate. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results.