Ed Mahon reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2024 Data Fellowship and received engagement mentoring and funding.

READING — Jessica Berry’s use of alcohol, fentanyl, and other drugs took a heavy toll, she recalled.

During her active addiction, she lost friends, had her young daughter temporarily removed from her care, spent time in and out of treatment centers, and was saved by an overdose reversal drug more than once.

One of her overdoses ended up in a news article, she said, and some of the online comments questioned why people like her were even worth saving.

“It really broke my heart,” she said at a public forum hosted by Spotlight PA in April. “But it also lit a fire in me.”

Over the past several months, I’ve worked to elevate stories like Berry’s as I’ve covered Pennsylvania’s drug addiction crisis and the conflicts around how to best use the state’s share of multibillion-dollar settlements with drug companies.

This work was boosted by an engagement grant through the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2024 Data Fellowship, which provided training, funding, and mentorship. I collaborated closely with Teena Apeles, the center’s national engagement editor, and Spotlight PA Events Coordinator Yaasmeen Piper for the engagement work. Much of this project — including organizing an in-person forum — wouldn’t have been possible or even attempted without them.

Here are five lessons from the work.

Have a clear reason why you want to prioritize engagement

Opioid settlement money is a natural issue for this type of engagement work. There are big stakes. Data show about 4,700 people died from a drug overdose in Pennsylvania in 2023, and many more are harmed in other ways.

Opioid settlement money is supposed to help. Pennsylvania expects to receive about $2 billion over roughly two decades as a result of settlements and litigation with multiple drug companies over their role in the opioid epidemic. Settlement payments through the state’s opioid trust began in 2022.

But, in Pennsylvania, we’ve seen big debates over how best to use the money, decisions made in secret, and policies that block the public from offering meaningful input. Last year, a first-of-its-kind national survey conducted by Spotlight PA and KFF Health News found 14 councils with responsibility over opioid settlement decisions routinely block members of the public from speaking at their meetings — including Pennsylvania’s opioid trust.

When WITF’s “The Spark” interviewed me and Kathleen Strain of Partnership to End Addiction about empowering community members, Strain described concerns across the state regarding settlement decisions.

“Families are often excluded from how these funds are going to be used,” said Strain, who has lost more than one family member to drug overdoses. “We’re not included in conversations.”

We decided to prioritize engagement work at Spotlight PA because we didn’t want to simply point out problems with the rollout of opioid settlement money here. We wanted to create opportunities for people most affected by the issue to get involved and share their own stories and solutions. This engagement work highlights that settlement money decisions aren’t made in a vacuum — they are determined by people with power using that power.

That engagement effort included asking readers to tell us their experiences of Pennsylvania’s opioid crisis. We ended up receiving about 75 responses through a detailed online questionnaire as a result. Family members, people in recovery, providers, and others all shared their experiences and perspectives.

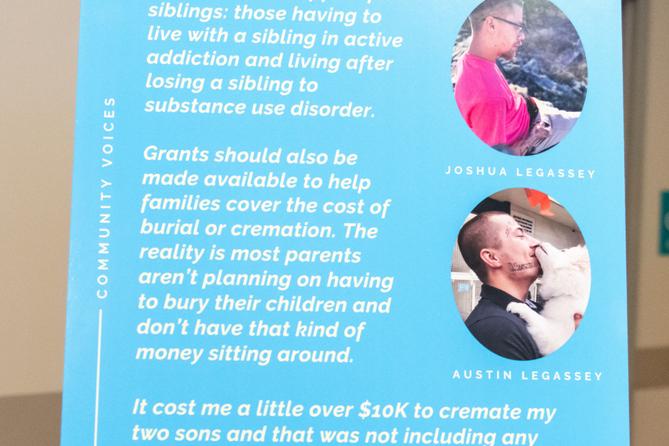

We turned some responses into posters, highlighting personal stories. We also invited some people to share their experiences as community speakers at an April forum in Berks County, about 60 miles from Philadelphia.

The opioid epidemic’s impact is so vast that we could have hosted the forum anywhere. But we chose Berks County for a few reasons: My news organization was working to open a new bureau there, in part to address concerns about a lack of access to trustworthy information in the community. Strain and one of the other experts we planned to partner with both happen to live there. It was close enough to me — about an hour’s drive away — that I could make multiple trips ahead of the event for a listening session, to hand out flyers and postcards, and to tour the health center that would host the forum.

Ahead of the event, Apeles had video or phone calls with our community speakers to help them prepare.

The approach we took for the event resonated. It “was a powerful night,” wrote Beckey VanEtten, one of the community speakers.

“One of the highlights for me was the participation and engagement from the audience,” she also wrote.

Other attendees offered similar feedback, highlighting how much they valued the personal stories, the open line of communication, and insight from other community members. Carla Sofronski, executive director of the PA Harm Reduction Network, said she left the event “feeling motivated and thinking of more ways to collaborate.”

We’ve also seen changes by those with power over settlement decisions. Pennsylvania’s opioid trust in February approved plans to hold a public listening session later this year.

In Maine, a former member of that state’s opioid council in December cited Spotlight PA and KFF Health News’ findings as she urged the council there to increase opportunities for public comment. Council members have since approved a policy for allowing regular public comment at their meetings.

“The Maine Recovery Council feels it is important that the people of Maine have a voice in the work of the Council,” the new procedure reads.

Putting searchable data in readers’ hands empowers them

For my first story as part of the Data Fellowship, I created a first-of-its-kind database that made it easier to track how Pennsylvania counties decided to spend tens of millions of dollars from their first rounds of opioid settlement payments — and whether a powerful state oversight board ultimately approved those decisions. Readers can search for terms like “police,” “advertising,” and even “soccer” and see what their local leaders are prioritizing.

There were two main benefits. For one, it’s not possible or practical for one reporter or even one newsroom to deeply scrutinize every opioid settlement decision. But by putting information in readers’ hands, we can allow them to reach out to their local officials if they have questions or concerns.

A former Republican congressman from the Philadelphia suburbs used our database and cited it multiple times as part of an opinion column in which he criticized spending the funds on projects that he said “do little to address addiction and treatment.” A nonprofit leader in Western Pennsylvania called it “amazing work.” A child welfare advocate praised our newsroom for “consistently shining a light where others have not.”

Secondly, the database was also helpful to me as a reporter. I used or cited it multiple times for my ongoing reporting. That included stories about counties fighting for more freedom over how to spend the money, a year-end review of the scrutiny and secrecy surrounding the issue, and an examination of the debate over using the funds to support child welfare agencies and efforts. I’ve also received a number of tips based on what others have seen in the database.

Experimenting with interactive approaches is worth the time

Inspired by candidate quizzes Spotlight PA has done for past elections, we created an interactive tool that let readers weigh in on real programs that were chosen to receive settlement money: improvements to parks and schools in Philadelphia, an outdoor youth and mentorship program in Somerset County, funding a detective position in rural Cameron County, and more. The feature was later highlighted by the Innovation in Focus newsletter from the University of Missouri’s Reynolds Journalism Institute.

“This tool makes a complex issue feel relevant and digestible for PA residents,” wrote Innovation in Focus Editor Emily Lytle.

We made our work interactive in other ways: I walked around Reading, passing out postcards in both English and Spanish that explained our coverage and sought feedback. (Spotlight PA’s democracy editor, Elizabeth Estrada, provided the Spanish translations, which were greatly appreciated by many of the folks I met up with.)

At the state Capitol, Apeles and I stationed ourselves at tables near the cafeteria on a busy day. We had sticky notes for people to write down where they thought opioid settlement money should go, and then they stuck them to a white poster. We displayed the posters highlighting personal stories at both the state Capitol and the Berks County forum.

One of the posters memorialized two of Erika Shambaugh’s children, who both struggled with addiction before their deaths. Later, she used a photo of herself holding the poster as her profile picture on Facebook. “Forever telling their stories,” she wrote.

Listening is action

Ahead of our February callout, we shared a draft of the language with a number of sources who represented families affected by the crisis, people in recovery, treatment providers, prevention experts, and more. They offered helpful suggestions, both on ways to clarify what we were asking for and to use language that would decrease the chances of turning people away.

For instance, rather than say “combat” and “crisis,” one person suggested we instead ask for “ways people are responding to this pressing issue.” Another suggested we include child welfare caseworkers in a list of front-line workers we wanted to hear from. A few offered additional questions to consider.

We also made some minor adjustments to the language to try to make it clearer that while our primary focus was the opioid epidemic, we were interested in stories and opinions regarding drug addiction issues more broadly.

We did this while still maintaining our independence — the final decisions remained up to us. But asking for feedback improved the form and, I believe, directly led some of the sources to share the final callout among their network.

For this engagement work, the tactics varied. But the message we’ve sent, I think, is clear: We have information and tools that can help our readers and sources. But we also can’t do this work without them.

Be prepared to be surprised

I’ve been reporting on the addiction crisis in Pennsylvania for Spotlight PA for nearly five years now. But I connected with many new sources through this engagement work, including Berry, whom we invited to be one of the community speakers at the forum after she filled out our online questionnaire.

Berry, who lives in Berks County, said she struggled with addiction for many years. She described feeling unsure whether she deserved another chance, and how the love of her young daughter motivated her to work hard to regain what she had lost and reinvent herself from scratch.

Berry’s daughter, Kylie Hammond, was removed from her care at the age of three, and Berry didn’t see Kylie for several months while undergoing drug and alcohol treatment. She ultimately got Kylie back full-time and has had her ever since, Berry told Spotlight PA. Kylie is 12 now, and she joined her mother at the Berks County forum.

In front of the crowd at Berks Community Health Center, Berry talked about how she’s working toward her master’s degree in mental health counseling and how she’s been able to give back to her community. She would like to see the opioid settlement money spent on harm reduction, transportation for treatment, early intervention programs, and other investments to save lives.

“I want this county to be a place where every person struggling has a fighting chance to get better, not because they’re lucky,” Berry said. “But because we made smart, compassionate choices as a community.”

One of the moments that surprised me — and I think others in the room — was during the question-and-answer session. Kylie was the first audience member to step up to a microphone.

“I’m really happy how a lot of people here are interested in using this money to help with children,” Kylie said, “because it is a big issue.”

Kylie was thankful, she said, for the people who are willing to help “to make sure that we live a long life.”