Spotlight PA’s reporting led to one family,

whose desperate situation mirrors that of thousands,

forced to make impossible choices by a system that failed them.

The Cost of Failing

Pennsylvania broke decades of promises to build a better system for people with mental illness. One mother's desperate fight to save her son shows the devastating consequences.

Sue, Robert, and Jonathan are pseudonyms. Their names and some details have been changed to protect their privacy.

When Sue thinks back on that cold spring morning in 2022, there are things she knows and things she doesn’t.

She knows her son Robert, who has had a serious mental illness for nearly a decade, turned up half-naked at her mother’s house, freezing, and in the throes of psychosis. She doesn’t know where he’d been or how he got there.

She knows she drove him home, tried to get him to take a hot shower, and put on warm, clean clothes. She doesn’t know why he refused.

She knows Robert begged for help getting to the hospital because there was something wrong inside his head. She doesn’t know why, when a state trooper arrived, he changed his mind.

She knows that after hours of erratic behavior, Robert agreed to go to the hospital if they called for an ambulance. She doesn’t know why, when he saw it arrive, he went for the knife drawer.

She knows she threw her body across the kitchen island in time to stop her son from ending his life.

She doesn’t know if she made the right decision.

“I just play this over and over in my mind.

Maybe I shouldn’t have taken that knife out of his hand.”

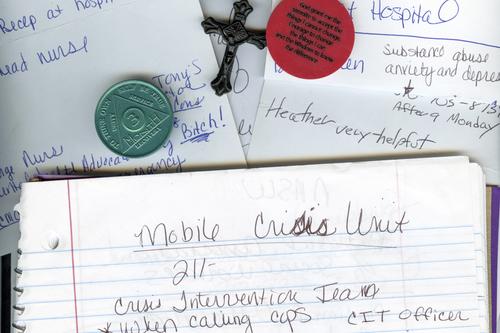

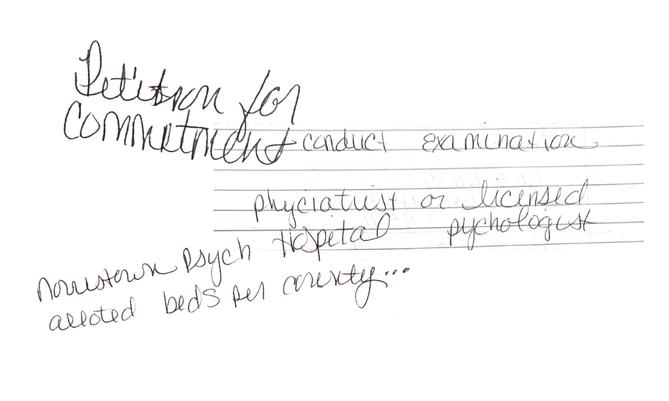

Handwriting excerpts throughout this story are from the notebook Sue uses to keep track of her attempts to get care for Robert.

By the time Robert was born in the mid-1990s, Pennsylvania had been closing its psychiatric hospitals for decades.

The hospitals provided intensive, publicly supported care for people with mental illnesses that were severe enough to interfere with everyday life.

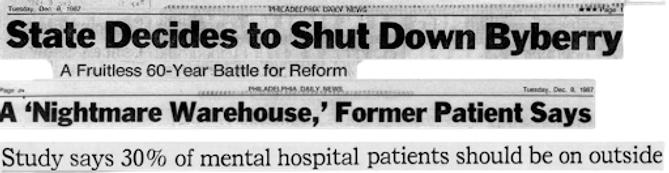

But by the late 1980s, some had become notorious for violence and abuse. Inside these institutions, even people who did not experience headline-grabbing conditions could languish for months and sometimes years beyond what their treatment required.

Some never left.

Persistent stories of barbaric conditions and patient deaths at Philadelphia State Hospital prompted a state investigation and eventual closure under then-Gov. Bob Casey Sr. Speaking to reporters during a teleconference in 1987, Casey previewed what would become the consensus around Pennsylvania’s state hospitals over the next three decades.

“We are not going to put these people out on the streets,” Casey said. “But we can no longer tolerate packing them into little more than a warehouse. Neither option is acceptable to me, nor should it be to a caring and civilized society.”

Studies following closures at Philadelphia and Allegheny County’s Woodville State Hospital showed that patients enjoyed far better lives when receiving care in their communities than while institutionalized.

In 1999, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed this sentiment in Olmstead v L.C., requiring states to provide people with mental disabilities access to community-based care.

Just over a year later, a group of psychiatric patients sued Pennsylvania to win their promised care. Like the plaintiffs in Olmstead, they were eligible for community treatment but remained institutionalized.

A federal appeals court sided with the patients in 2004 and directed Pennsylvania to create a plan to release them. But a year later, the case was again in front of that court and the patients were still in the hospital.

In his ruling, appellate Judge Max Rosenn commended Pennsylvania for reducing the patient population from nearly 40,000 in the 1950s to just 3,000 in 2000. But his opinion was scathing in its assessment of the commonwealth’s plan to deinstitutionalize the rest of the state hospital system: It amounted to no plan at all.

The state’s cornerstone program for getting patients — and the funding supporting them — out of state hospitals also showed little promise, Rosenn wrote.

Called the Community Hospital Integration Project Program, or CHIPP, it was established in 1991 to preserve the dollars used to run state hospitals for use in the community.

But while it initially identified concrete goals and benchmarks — such as downsizing the system by 250 beds a year and closing the civil wings of three hospitals — the department “inexplicably” failed to follow through on the steps laid out to reach them, Rosenn wrote.

CHIPP was never intended to be the last word on what the commonwealth planned to do in serving Pennsylvanians with mental illness, the state argued. It was just a first step. In fact, it was a framework for future steps.

But Rosenn wasn’t convinced and pushed the state to act, not just plan: “General assurances and good-faith intentions neither meet the federal laws nor a patient’s expectations.”

Raising Robert was easy.

Sue remembers a meticulous kid who was careful about maintaining his curly hair, but effortless in the way he moved through his life.

A natural student, his name regularly appeared in the local paper alongside other classmates who made the honor roll.

A gifted, third-generation athlete, he stunned spectators when he won a match against competitors more than twice his age.

A good brother, Robert teased his siblings, who unlike him, needed reminders to grab their backpacks and do their homework.

Sue was there for it all. A self-admitted helicopter parent, the single mom chaperoned every field trip and went to all the games and competitions and recitals, content to sit in the audience by herself if it meant supporting her children.

If the kids forgot their gym clothes or an assignment, and Sue knew they’d have to miss recess to make up for the infraction, she’d miss work to take whatever they needed to school.

“If they were having a bad day, I was having a bad day,” Sue said.

Robert, the oldest, made the constant effort feel worth it. “Everyone loved him,” Sue said, “the kids and the older people.”

At his competitions, he would sign autographs on frisbees and hats and throw them into the stands. On errands around their small town, he was like the mayor. “Everywhere we went, they'd be yelling, ‘Hey, Robert! Curly, hey!’ And I'd say to Robert, ‘Who's that?’ And he'd say, ‘I don't know.’”

He spent summers swimming at the nearby lake and occasionally at his aunt’s pool with his siblings and his cousin Jonathan. He was a good friend and son, a rock for Sue, especially after she divorced his father early in his childhood.

He graduated high school with honors, enrolled in a nearby university, and began working toward a degree.

His next 20 years seemed as certain as his first.

Despite Rosenn’s misgivings, Pennsylvania made progress in the years following his ruling.

In 2005, the state published “A Call for Change,” a 74-page document describing the radical transformation needed in the mental health care system.

In the years after, officials brought together the people who would need to buy into closing state hospitals — providers, advocates, unions representing hospital workers, and most crucially patients with lived experience.

And for a short while, CHIPP worked.

Under former Gov. Ed Rendell, Pennsylvania closed three more hospitals: Harrisburg in 2006, Mayview in 2008, and Allentown in late 2010.

Following each closure, funding for community supports increased.

People with jobs as providers or staff within the institutions took other positions within the state government. Those with lived experience managing a mental illness found jobs as peer specialists, working with people still in crisis. The state also formalized standards for community treatment teams: groups of mental health staff that would mobilize to help people with complicated and serious needs.

Those days were extraordinary, said Joan Erney, who oversaw the hospital closures as deputy secretary of the Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services.

It was joyful, she said.

“I think that we all felt extraordinarily optimistic about the future of the program.”

In 2009, President Barack Obama directed the U.S. Department of Justice to prioritize enforcing the Olmstead decision. Shortly after, Pennsylvania published its first Olmstead plan, a written blueprint for how the state would build on the momentum.

The document outlined the kinds of goals and deadlines Rosenn had wanted to see state officials commit to.

Slightly less ambitious than prior plans, the new one nevertheless showed the state’s commitment to progress: It would use CHIPP to close 90 beds a year. The state funds previously used to support those beds would continue to flow into the community. Counties would develop their own mini versions of the plan to ensure follow-through.

The next 10 years seemed as promising as the last.

Slowly, and then all at once, Robert started to change.

He had always been health-conscious, Sue said, but his preferences grew peculiar.

He started avoiding the microwave and eyeing his mother suspiciously when she used it. Robert’s once-diligent grooming regimen of showering and changing clothes multiple times a day began to slip.

His first year of college became stressful when he became a father. Robert was the same age as Sue when she had him.

Then, his cousin Jonathan died.

Jonathan met up with Robert while visiting home during his first semester in college. On his way back that night, Jonathan fell asleep at the wheel and drove off the road. Robert was likely one of the last people to see him alive.

Looking back on the decade that followed, Sue sees this moment as an inflection point in not only her son’s life but her own. As grief and guilt began to unravel her son, navigating Pennsylvania’s disjointed mental health system began to unmoor Sue.

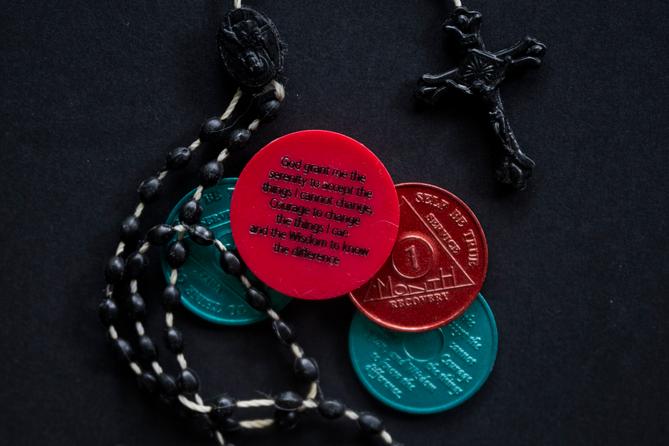

Months after Jonathan’s crash, Robert was in one of his own. The resulting DUI led to a stint in a nearby rehab. The structure helped, Sue said, and Robert became a leader at the facility, helping clean out the chapel so he and the other people enrolled in the 12-step program could have somewhere to pray.

But even when Robert was sober, emotional hardships would trigger setbacks, Sue said.

She watched as the corkscrew curls Robert maintained so carefully as a teenager grew long and tangled. He dug a crater into his palm, convinced pencil graphite embedded in his skin from some long-forgotten schoolyard shenanigans was causing his mind to betray him.

As Robert began to cycle in and out of paranoia and psychotic breaks, the next years of Sue’s life became dominated by unspeakable choices.

Should she help her son, even as he burrowed further into distrust and sent her texts full of bile and accusations? Should she spend her days and nights on the phone with the county mental health office, with lawyers, with the governor's office, with kind but unhelpful people who told her over and over, “I’m sorry” and “the system is broken” and “this is just the way it is?”

Or should she give up?

Should she lock her doors, stop the phone calls, and let her son continue to sink into destabilizing paranoia, whatever the consequences?

Should she let Robert go?

Former Gov. Tom Corbett’s 2013 budget was catastrophic for county mental health departments.

The 2008 economic recession had taken its toll on Pennsylvania. State revenue plummeted when the market crashed, and by Corbett’s second year in office, federal stimulus dollars had dried up. Left with state spending in excess of the revenue coming in, and unwilling to raise taxes on state residents, Corbett took a hard-line on spending.

He initially targeted Pennsylvania’s public schools and universities, but uproar following the proposed cuts sent Corbett and the Republican-controlled General Assembly searching for other targets. They found them in social services for groups with less political capital, among them Pennsylvanians with severe mental illness.

He stands by those choices.

"The 2013 budget decisions, made over a decade ago, reflected the economic realities of that time,” Corbett told Spotlight PA in a statement. “We aimed to balance compassion with fiscal responsibility, and I stand by the tough but necessary decisions we made to steer Pennsylvania through a fiscal crisis.”

Nevertheless, the results were devastating.

For years, Pennsylvania has required counties to provide mental health services but provided most of the funding to do so. Alongside the money the state sent counties as it closed hospitals, it also provided so-called base dollars. That funding allowed counties to create services for vulnerable people who either do not qualify or are not signed up for medical assistance.

The dollars also fund services, such as housing, transportation, and case management, that aren’t covered by private insurance and public medical assistance but can be crucial for people who have serious mental illness.

Before the Corbett cuts, that funding flowed through a discrete program alongside funding for other social services. To lessen the blow, the administration offered a block grant that combined the programs, creating one cash infusion counties could use for different needs.

For counties that chose to use the grant, the flexibility provided some help but couldn’t paper over the reduced funding.

But even as voters, frustrated with the austerity of the Corbett administration, selected Democrat Tom Wolf to lead the state, the money did not return.

With fewer dollars, counties offered fewer services and reached fewer people.

As progress toward the grand vision slowed, a tension emerged.

The state had a federal mandate to sunset its inadequate state hospital system.

The county governments, mental health administrators, and clinicians needed somewhere to place the most serious patients, the ones their increasingly meager services could not fully support.

And there were fewer of those beds than ever.

“Put her on the fucking phone.”

The blood was pounding in Sue’s ears, her hard work evaporated by a shower and a book.

Robert had been kicked out of another treatment facility. Convinced electricity was poisoning him, he ripped outlets from the walls. Or had he thrown the vacuum? Or was this the one where he mopped the carpet?

The cycle was always the same regardless of the details: Robert, unable or unwilling to find mental health services, checked into a drug and alcohol treatment facility. Without appropriate psychiatric care, he behaved erratically, sometimes violently. The facility, unwilling to keep him in treatment, took him to the hospital. Once there, he’d be held temporarily but discharged to the street relatively quickly, where he’d call Sue to pick him up.

This time, though, she’d worked with a case manager at a nearby hospital, who pulled strings to find Robert placement in an inpatient mental health treatment program near Philadelphia.

Maybe they could stop the cycle.

When Robert arrived at the hospital from the treatment facility, he’d been psychotic and covered in feces that he had smeared on the walls. To get him to the program, he’d need to be involuntarily committed. But when the assessor arrived to determine whether he could be, Robert had showered and was reading in bed.

He was stable — for the moment.

Seeing that, the assessor decided Robert was no longer a danger to himself or others. His spot would go to someone else in more apparent need.

“What!?” Sue said she asked the assessor over the phone. “People had to jump through hoops to find placement for him.”

Incensed, she asked the woman if mental illness only affects people who are illiterate.

“I was like, really? That is your deciding factor? He can read?”

Hospital, community, relapse, homelessness. Or worse.

Scott Baldwin has been the mental health administrator for Lawrence County since 2020. Over that time, he’s watched residents repeat this pattern over and over.

But for people with serious mental illness, it’s not just a pattern, “that's the system,” Baldwin said.

In the decade since the Corbett cuts, Pennsylvania has not closed a state hospital — with the exception of the civil wing of Norristown — halting the progress of the late 2000s and early 2010s. But until recently, the state has also not increased funding for community care..

“We make these promises to these people that are coming out of these institutions, and we're given a pittance to be able to support them in the community,” said Miki Drutchal, the mental health administrator for Lackawanna County.

In rural counties with smaller populations spread across wide areas, limited state funds overburden the few existing programs; some even have to share their resources with neighboring counties, further stretching their reach. This in turn affects hiring: Attracting and retaining clinicians in these areas is a struggle, especially as fewer dollars are available to entice them.

“I have to beg providers to come and provide service in Greene,” said Brean Fuller, the county mental health administrator.

In 2024, for the first time in over a decade, struggling counties received more state money for mental health.

Gov. Josh Shapiro proposed and the legislature approved a $40 million increase in county base funding in his first two years in office.

Spotlight PA sent a detailed list of findings to the Department of Human Services and Shapiro’s office. In response, DHS spokesperson Brandon Cwalina sent a statement.

“The Shapiro Administration has consistently proposed new, significant investments in mental health resources across the Commonwealth – and worked in a bipartisan manner with the General Assembly to deliver the most meaningful increases in mental health funding in years,” he wrote.

The statement also highlighted Shapiro’s executive order creating a Behavioral Health Council to improve collaboration between government agencies and others involved in the mental health system.

“We are further working with all involved parties, including counties and the General Assembly, to find short- and long-term solutions,” Cwalina said, “especially prevention and diversion strategies that can help strengthen this system.”

Shapiro has proposed an additional $20 million in his 2025 budget, as well as additional investments in community-based care and step-down programs for people in state hospitals.

So far, the infusions have not reversed years of underfunding.

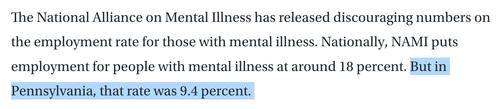

Spotlight PA partnered with the Lehigh Valley Justice Institute to analyze mental health income and expenditure reports from all 67 counties between fiscal years 2017 to 2023, the most recent year available from the Department of Human Services.

The analysis found counties are doing less with less. Between 2017 and 2023, statewide spending on mental health declined by roughly $147 million. Over the same time, mental health services reached fewer people statewide, declining from about 435,000 people served to under 350,000.

The lack of mental health resources is especially stark in communities, like Lawrence County, that do not have access to one of the remaining six state hospitals.

After Mayview closed in 2008, the county received CHIPP dollars to offset the closure, funds that were expected to be untouchable. But the state slashed that money under Corbett as well, Baldwin said. The few state dollars Lawrence County does receive go directly to long-term supported housing for people who have high-level needs and likely always will. But those beds are limited and expensive, Baldwin said.

If county support isn’t available for someone with long-term need, private facilities may not be an option either.

In a system where high acuity care is largely privatized, Baldwin said, “You'd be surprised how many hospitals will just say ‘This is a difficult case. I can't handle this behavior.’ So, then what?”

When Sue grabbed the knife out of Robert’s hand, the kitchen exploded into chaos.

The state trooper dove onto Robert and Sue, yelling and fumbling for his handcuffs. Unable to grab Robert’s wrists, the trooper shackled his bare ankles.

Sue pleaded as Robert writhed underneath her and beat against the trooper, who radioed for backup.

“He did not go after you or me with this knife,” she shouted, desperate to keep Robert from being shot. “Say it out loud: He was going to slit his own throat.”

The trooper repeated her words, and Sue broke free from her son. The officer pulled his Taser, shocking Robert twice.

But Robert fought on. He managed to get upright, continuing to grapple with the officer. Then Robert lunged at Sue, knotting his fingers in her hair.

The three tumbled through the kitchen door, onto the porch. Officers stood on the lawn, weapons drawn.

Sue screamed to the nearby EMTs for help. Police wrestled Robert to the ground, ripping out the chunks of Sue’s curls still tangled in his fingers.

The medics sedated Robert once, then twice, as he struggled against his mother, the strangers on the lawn, and the chaos in his head.

His body went limp, but his eyes fixed on his mother.

Sue watched the responders load her son into the ambulance, Taser prongs still embedded in his back.

Pennsylvania had an opportunity to help its struggling mental health system.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the state received billions of dollars through the American Rescue Plan Act, funds that supported everything from rental assistance to local infrastructure projects.

In 2022, the state legislature set aside $100 million to support the adult mental health system that had become strained as more and more state residents reported mental health needs during the pandemic.

A commission tasked with studying the mental health system found it not only stressed and disjointed but increasingly replaced by the justice system.

“The Department of Corrections and county jails have unintentionally become the largest providers of behavioral health services in the Commonwealth and are not sufficiently prepared and resourced to meet this population’s needs,” the commission found.

Spotlight PA’s findings back this up.

PrimeCare, a private contractor that provides health care to 37 jails across Pennsylvania, supplied Spotlight PA and the Lehigh Valley Justice Institute with 10 years of mental health care data.

An analysis by the newsroom and the research group found that of people who jail staff screened for mental health needs, more than 60% needed services while incarcerated.

As counties do less with less, the state’s local jails have seen an increase both in the number of detainees needing mental health services and the seriousness of their need, even as jail populations have declined.

The company uses four categories to classify the mental health needs of people in jail, ranging from those with no history of mental illness to those with serious diagnoses and significant needs.

Between 2017 and 2022, the share of incarcerated individuals placed in the two most serious categories grew by roughly five percentage points respectively.

Between 2014 and 2022, the rate of jailed individuals on suicide watch per 1,000 has more than doubled. In the same period, the percentage of the daily adjusted population on psychiatric medication has increased from under a quarter to roughly 40%.

In 2022, Spotlight PA surveyed the leaders of more than 20 jails across Pennsylvania. The respondents — wardens and local government officials tasked with overseeing jails — said jail can be a costly and harmful path for individuals who come to the facilities because of crimes that are likely a symptom of their mental illness.

But in Pennsylvania, jail is often the only place that can house a person whose symptoms have resulted in a call to police.

In response, counties have also had to find funding for services within the justice system: co-responder programs aimed at diverting 911 calls about mental health crises away from police, crisis intervention training for local police departments, and “forensic” case management for people whose mental health has entangled them in legal trouble.

The mental health commission report recommended directing $23.5 million of the federal pandemic relief funds to the justice system to pay for care for incarcerated people, services for those leaving jails and prisons, diversion programs, and crisis intervention training for police and emergency responders.

The report argued the rest of the $100 million should sustain the mental health workforce, create more services, and integrate the mental and physical health systems.

But in 2023, the first year of Shapiro’s term, the money was diverted at the last minute to support school mental health and safety initiatives, part of a budget deal struck between the Democratic governor and the Republican-run State Senate.

The elusive dollars, once again promised, were ripped away.

Despite her years of work, it wasn’t Sue who ultimately found a place for Robert.

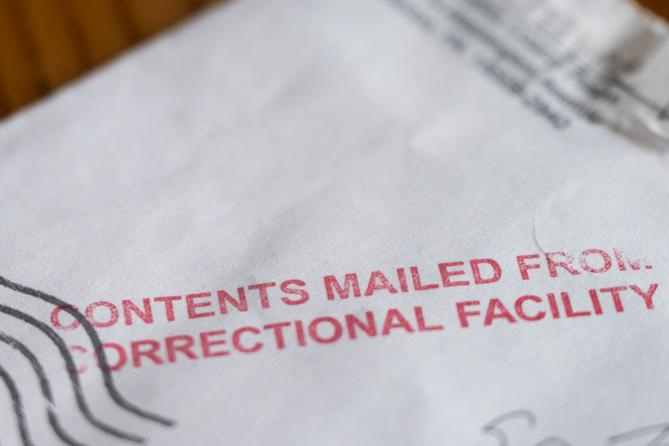

Hours after he arrived at the hospital, medical staff cleared Robert for discharge. Troopers, alarmed at the prospect of releasing him to the street, booked him at the local jail.

At first, Sue felt an uneasy relief.

She didn’t have to worry if her son was cold, if he was on the side of the road, if he was going to overdose.

But her relief curdled into guilt as Robert sat in jail for days, then weeks, then months.

While incarcerated, he attempted suicide again. He spent months in solitary confinement under behavioral surveillance, where he continued to fall apart.

Because of his unstable mental health, officials worried Robert couldn’t aid in his own defense. A county judge stayed court proceedings until Robert could get a competency assessment.

He never did.

Robert spent more than a year in jail. He was released only after Sue reached out to a friend with connections in the county.

Those first few days felt jubilant to Sue. Robert seemed stable and focused on restarting his life. He checked into court-ordered inpatient treatment for 30 days, and once released, started doing virtual therapy sessions from home. He bought a car. He was holding down a job.

But the peace was tenuous.

Robert had achieved some stability from treatment in jail, but he also brought home the trauma of months spent alone in a cell. He wouldn’t eat sitting down. He spoke to Sue only in short bursts.

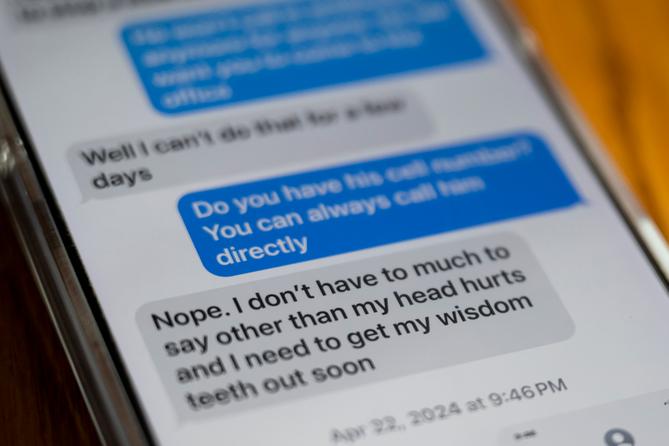

After an oral surgery, Robert went home with a prescription for an opioid painkiller.

“And then he ended up on my roof,” Sue said.

The drug triggered a psychosis that lasted even after Robert stopped taking it and tested clean for a probation officer. Over the next few months, he spray-painted windows black. He smashed appliances. He accused Sue of poisoning him. He left.

Getting her son back felt like a miracle. Losing him again felt like a death.

“I think the thing that hurts me the most is not just the pain that he's going through, but the fact that he thinks I'm a co-conspirator,” she said. “I'm the only one that's had his back. I'm the only one, and he thinks I'm capable of doing this to him.”

Sue mostly lost track of Robert, but she never stopped trying to find solutions.

So when her mother called again one night in 2024, she grabbed the purple spiral notebook full of names and phone numbers, evidence of her years of advocacy on her son’s behalf. She flipped to the page where she’d taken notes on what state and county officials told her to do if Robert showed up again in crisis.

She dialed 911.

“I need a crisis intervention team,” she told the dispatcher.

“What county, ma’am?”

She told him. The dispatcher paused, and put a local police officer on the line.

Sue repeated her request, growing more frantic.

That’s only in the nearby city, he told her, not the small township where Robert was once again banging on his grandmother’s door, demanding money.

Sue recounted all the officials and mental health advocates who told her to ask for crisis intervention — the names of all the people written in her purple notebook.

“I don't care who told you what,” he said.

“I'm telling you, we have nothing like that here.”

Correction: A chart in this story has been updated to accurately reflect the inflation adjusted mental health base funding for each year in the data.

Coming soon: Inside the downfall of the state’s CHIPP program