This story first appeared in PA Local, a weekly newsletter by Spotlight PA taking a fresh, positive look at the incredible people, beautiful places, and delicious food of Pennsylvania. Sign up for free here.

Fewer Pennsylvanians ride the state’s rail these days, but a network of train lovers work like locomotives to preserve the commonwealth’s rich railroad heritage.

From small exhibits in former rail cars, to a site run by the National Park Service, to a 100,000-square-foot state-chartered museum, organizations statewide make this history accessible — and even rideable.

Craig Sansonetti, president of the Ma & Pa Railroad Preservation Society, leads one of those groups.

He’s been mesmerized by trains since childhood, when his family owned a property that abutted the Maryland and Pennsylvania Railroad. The short line once connected Baltimore, York, and dozens of small communities between them.

The young Sansonetti’s fascination with the railroad was so intense that he and his grandmother hopped on its very last passenger train in August 1954. Over 70 years later, the “Ma & Pa Railroad” — as it’s affectionately nicknamed — remains one of his passions.

“There was urgency to do something before the track was torn up and gone,” Sansonetti said of the preservation society’s formation in the 1980s, which began when 31 people teamed up to buy a section they still maintain.

Today, the volunteer-run nonprofit has 60 active members who work together to operate a “heritage village” in York County, where they teach visitors about the railroad’s ties to local history, and run excursions on the track it maintains.

PA Local spoke with workers and volunteers statewide about their passion for train history, and Pennsylvania’s special connection to railroads.

“You can’t talk about Pennsylvania history without talking about railroads,” Patrick Morrison, director of the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania, told PA Local. “It’s almost baked into the history, or the DNA of Pennsylvania as a modern industrial state.”

Building Pennsylvania

Railroads started being built in the commonwealth around the 1830s, and within two decades, Pennsylvania led the nation in their development. As the state’s rail network expanded, industries like coal, iron, and lumber grew in kind, as trains enabled those resources to be transported nationwide.

The rails boosted some communities, and birthed others.

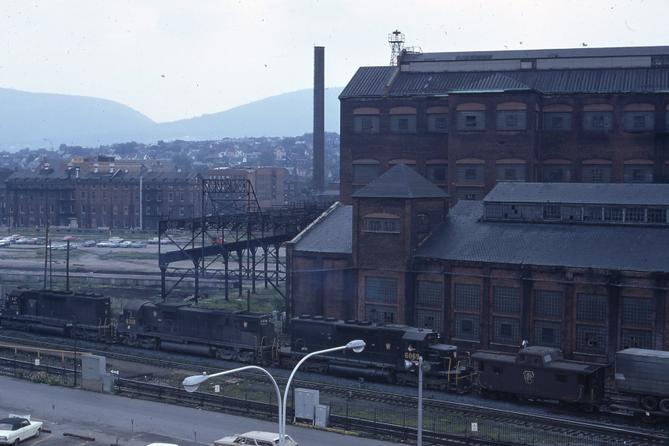

One major example is Altoona. The Blair County city was developed by the Pennsylvania Railroad because of its proximity to the Horseshoe Curve, an engineering marvel that opened up rail travel across the Allegheny Mountains.

Altoona became home to one of the railroad company’s main shop complexes, and eventually one of the largest repair operations in the world. During its heyday in the 1920s, the Pennsylvania Railroad employed around 16,500 people there.

“The railroad literally built the community of Altoona, and without the railroad, I would say there would be no Altoona,” said Matthew Wolff, curator at the city’s Railroaders Memorial Museum.

Located across the tracks from Altoona’s present-day Amtrak station, the museum tells the story of local employees — “the conductor, the engineer, the brakeman, the shop workers” — across three floors of exhibits, Wolff said.

Decades after the Pennsylvania Railroad folded, plenty of Altoona locals know or are related to former workers, said Wolff. While the museum can’t offer specific information about visitors’ family members who worked for the railroad, it can still teach them about what the job was like in that era.

“In a way, you can make a family connection through these stories,” Wolff said. “It keeps family stories alive for younger generations who have an interest in the railroad, or might have an interest in doing family research.”

Museums large and small

Pennsylvania’s rail history draws enthusiasts from all over.

The Railroad of Museum of Pennsylvania in Lancaster County, which opened in 1975, sees around 85,000 and 90,000 visitors per year, Morrison said.

The state-created museum — a massive hall with over 100 real locomotives and railroad cars, plus numerous photos and artifacts — boasts on its website that it is “the first structure in North America built specifically as a railroad Museum.” Over its 50 years of existence, it has doubled in size, given its exhibits a makeover, and started constructing a 16,500-square-foot roundhouse exhibit building.

The Railroaders Memorial Museum is comparatively smaller, but draws between 30,000 and 40,000 visitors a year, Wolff told PA Local — including lots of people from out of state, as well as international tourists from other historic train hubs like England, Germany, and Japan.

Smaller rail museums don’t get as much traffic, workers told PA Local.

At the Ma & Pa Railroad Heritage Village, school visits help familiarize locals with the site, said Sansonetti.

But despite social media posts and posting flyers in nearby areas, he said, “We still have people who live not too far away who come by and say, ‘Gee, we never knew you were here.’”

Newtown Square Railroad Museum in Delaware County, home to several historic rail cars, faces the same dilemma.

Although the group promotes the museum through social media and co-hosts a festival with the local parks and recreation department every year, the site is still a “mystery” to some people who’ve lived in the area their whole lives, president Fran Franchi told PA Local.

“The challenge is that we need to grow the volunteer base and grow the donations,” Franchi said. “The challenge is keeping up with the maintenance on all of these cars.”

Volunteer-powered

Everyday enthusiasts willing to dedicate their time are the coal in the engine of rail preservation and education.

Newtown Square Railroad Museum was started by two local history buffs, Sam Coco and Jack Grant, who wanted to fix up the town’s abandoned freight station building.

It’s now run by a small group of volunteers like Franchi, who got involved about a decade ago. A friend convinced her to join, and a fondness for trains — like those on the former Reading Railroad, which she remembers riding to and from Pottsville as a child while her uncle, a conductor, looked after her — helped win her over.

“I like trains,” Franchi said. “I just think they’re cool. But it’s important to keep the history for the future, for the people that are here now, for their children. There’s so many families that come and visit, and the kids just love trains.”

East Broad Top Railroad, a heritage railway and National Historic Landmark in Huntingdon County that draws around 35,000 riders per year, also has a robust base of volunteers. Its 1,500-member-strong “friends” group helps with maintenance and fundraising, said Rick Hamilton, the railroad’s marketing director.

The Friends operate a nearby museum about the railroad, and some members — some from as far as California and South Dakota, Hamilton said — come to East Broad Top to paint, restore windows, and perform other maintenance and preservation work.

“Whatever needs done, they’ll do it,” Hamilton said.

Even the state’s flagship museum, which employs around two dozen paid workers, also has 150 active volunteers who help restore rail cars and locomotives, catalogue archival materials, give school tours, and greet visitors.

Volunteering is how Morrison, the museum’s director, first got involved there almost three decades ago.

“It’s a pretty important part of what we do,” Morrison said. “We can’t do this without them.”

Connections to past and present

Rail travel isn’t what it used to be. After World War II, passenger service was supplanted by alternatives like cars and buses, and the patchwork of railroad companies that operated across Pennsylvania eventually went bust.

Despite that decline, railfans say it’s important to acknowledge trains’ part in building local economies and communities.

“Today’s children know more about the Revolutionary Era than they do about the time in which their great-grandparents lived, but transportation is key to all kinds of historical developments,” Sansonetti said. “The role that railroads played — and not just big trunk-line railroads, but railroads like the Ma & Pa in developing these communities — is a story that needs to be remembered.”

Of course, trains do still help sustain today’s economy, especially the manufacturing and energy sectors, with Pennsylvania having more operating freight railroads than any other state. And Amtrak links cities nationwide.

Rail museums make these important systems less invisible, said Morrison.

“We try to make sure that folks know how important and how connected they are, even though they may not have ever taken a train before,” he said.

“I’m willing to bet the products they buy in the store, at least some of them were probably delivered to that store by a truck that met a train … so at some point there’s a railroad in the story.”

Correction, July 25, 2025: The lead image caption has been updated to note the pictured mill was a flour mill.