HARRISBURG — Pennsylvania wants to continue categorizing a class of powerful synthetic opioids as Schedule I controlled substances to allow state prosecutors to charge suppliers as use rises.

Nitazenes are up to 50 times as powerful as fentanyl and are often used to adulterate other opioids, which increases their potency and poses a serious overdose risk.

Use has been increasing since 2019, Mark O’Neill, a state Department of Health spokesperson, told Spotlight PA. In response, the department issued a temporary scheduling of nitazenes for the first time in 2023, and is in the process of doing so again.

Pennsylvania law allows the secretary of health to temporarily schedule drugs using an abbreviated process if there is an “imminent and continued hazard to the public safety.”

Nitazenes are already illegal at the federal level, with some forms of the drugs first scheduled by the Drug Enforcement Agency in 2020. Scheduling it at the state level allows Pennsylvania to also prosecute people for selling or possessing the drugs.

The Pennsylvania health department has confirmed at least 50 fatal overdoses associated with nitazenes since 2020, with a record 29 deaths just last year.

By comparison, fentanyl was associated with the deaths of more than 3,500 Pennsylvanians in 2023 alone. However, official nitazene overdose numbers likely don’t capture the full scale of the problem.

“Their true prevalence is really unknown in large part due to lack of testing and reporting,” Alex Krotulski, director of the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education, told Spotlight PA.

The Montgomery County-based lab studies toxic adulterants added to drugs and acts as a warning system for emerging illicit substances (federal funding for that program was recently frozen). It also tests samples for the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

While people often use test strips to ensure drugs don’t contain fentanyl, those strips don’t detect nitazenes. And Krotulski said not all medical examiners and coroners are testing for nitazenes either.

The state health department issued a statewide alert about the drug to health care providers last year. O’Neill said the agency surveyed labs that can test for nitazenes when a person dies of an overdose, and found that 80% look for the substance as part of a standard panel.

He did not answer a follow-up question about how many Pennsylvania labs, coroners, and medical examiners aren’t testing for the drugs.

Carla Sofronski, executive director of the Pennsylvania Harm Reduction Network, said scheduling alone doesn’t solve the problem.

“While these policies are well-intentioned, they often cause more harm,” she said, arguing that criminalizing drugs leads users to find alternatives that can be more dangerous and can make the drug market more unpredictable.

Expanding access to the opioid overdose-reversing drug naloxone and increasing awareness of the danger of synthetic opioids would be a more effective approach, she said. (Experts warn that more than one dose of naloxone may be needed because of the potency of nitazenes.)

Education on nitazenes “for medical professionals, by medical professionals” is needed, especially in emergency rooms, she said.

Rising deaths

Nitazenes were first created in the 1950s as an alternative to morphine, but they were never introduced to the market because their potency introduced a high risk of overdose. Different forms range from less potent than fentanyl to upward of 50 times its strength.

At least 2,000 deaths have been associated with nitazenes nationwide since 2019, according to the DEA.

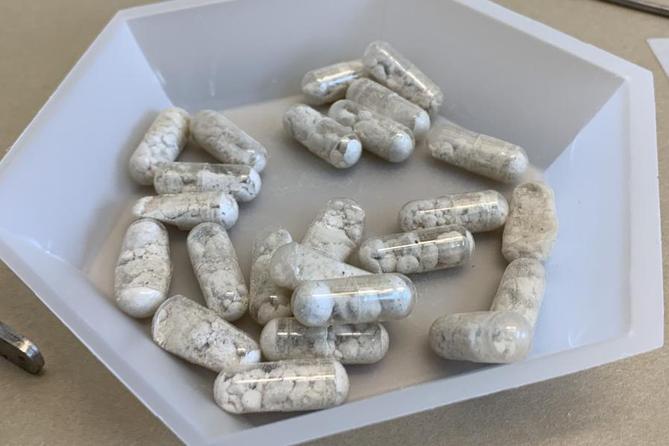

They emerged in the American illicit drug trade only recently, first detected in 2019. Forms of the drug have also circulated in Australia, Canada, and parts of Europe. They can be consumed by inhalation, injection, or swallowing a tablet.

The U.S. nitazene supply primarily originates in China. Upon arrival here, the drugs are either mixed into other opioids like fentanyl or sold as another opioid, without the buyer’s knowledge, Krotulski said.

“Almost no one probably understands that the drugs they’re buying have nitazenes in them alongside fentanyl, or the fentanyl has been replaced by nitazenes,” Krotulski said.

Nitazenes were identified in at least 4,300 law enforcement drug seizures between 2019 and 2024, according to a report by the Organization of American States, an international coalition that promotes cooperation among North and South American countries and studies regional trends in health, politics, and economics.

Krotulski hopes that trafficking from abroad slows following China recently moving to criminalize nitazenes. Chinese bans on many fentanyl analogs in 2019 and synthetic cannabinoids in 2021 significantly impacted the drug trade into the US.

“If history … is any indicator, generally, the laws that China passes have extreme impacts on drug suppliers,” he said.

Still, nitazenes continue to pose a public health threat, with effects including sedation that can disorient users and difficulty breathing, which can prove fatal.

Vincent DiFonzo is an intern with the Pennsylvania Legislative Correspondents’ Association. Learn more about the program. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results.